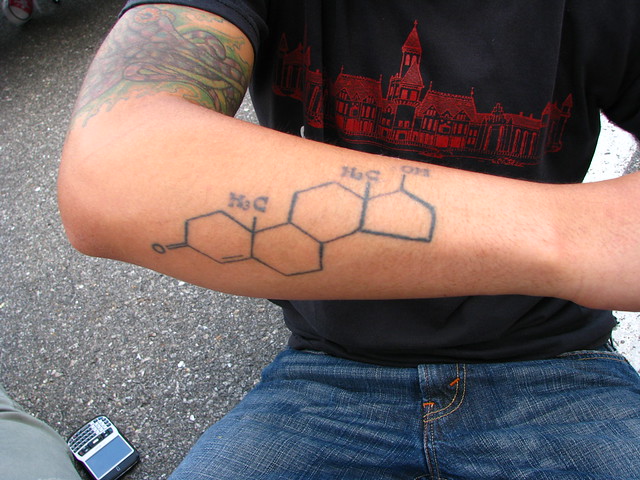

Last month, a study was published which reveals that men who take care of their babies get a big drop in testosterone levels. The more involved they are with their kids, the bigger the drop.

These findings certainly corroborate with my experience. Testosterone is associated with selfishness and aggression, and in the months and years following the birth of my daughter, I’ve been feeling the opposite. The authors theorize this may be a survival mechanism. Lower testosterone levels may make men better fathers and also protect them from chronic diseases.

I buy it.

So could all this, everything I’ve been feeling of late come down to a shift in hormones? A hardwired evolutionary development?

Perhaps. And yet: An overly mechanistic view of psychology is highly problematic. Such explanations can be powerful but also powerfully disenchanting, even depressing. It’s the fallacy of reductionism, I think, a fallacy in which I’ve participated for many years.

I even wrote a triolet on the subject back in the late 80s.

I admit it! My mind is a machine.

But really, I’m comfortable with that.

So I tick tock tick talk what I mean.

I admit it! My mind is a machine,

just like my watch, but so is everything.

I work much like a thermostat.

I admit it, my mind is a machine,

but really, I’m comfortable with that.

I’m coming to understand that I am guilty not only of bad poetry but also bad philosophy. The human psyche is certainly more than the sum of its parts. I’ve been reading a bit about emergence and emergentism, and it’s fascinating stuff.

Probably I am mangling this badly, but I’d describe emergence as the idea that seemingly simple components can interact to generate complexities of another order entirely. This offers an alternative to the mechanistic model. Mind can be seen to emerge from the biological brain almost as a new dimension of reality.

In an essay titled “The Sacred Emergence of Nature,” Ursula Goodenough and Terrence W. Deacon write:

Reductionist understandings of how minds work are fascinating, but they are also irrelevant to what it’s like to be minded. While we don’t know what it’s like to be a bat, we know what it’s like to be a human, and it entails a whole virtual realm that doesn’t feel material at all. The beauty of the emergentist approach to mind is that it suggests that to experience our experience without awareness of its underlying mechanism is exactly what we should expect from an emergent property. The outcome has been given reverent names, like spirit or soul, names that conjure up the perceived absence of materiality. But we need not interpret this as evidence of some parallel transcendental immaterial world. We can now say that the experience of soul or spirit as immaterial is simply a reflection of the way the process of emergence progressively distances each new level from the details below.

To extrapolate, the extraordinary cognitive shifts I’ve experienced after the birth of my daughter may well have substantive biological underpinnings, but to focus on those to the exclusion of all else would be to miss the point entirely.

One could say that I lost some testosterone but found my soul — while still maintaining a naturalistic worldview.

Photo: IMG_4151.JPG / Yutan / BY-NC-ND 2.0

Be First to Comment